fontFeatures and the "OpenType CPU"

Recently I’ve been working on a new idea which I think is worth sitting down and explaining carefully. It started out as a way to represent the layout features inside an OpenType font so that they could be manipulated programatically, rather than having to shuffle little bits of AFDKO code around. But it’s kind of grown a bit since then, as ideas tend to do.

The Problem

Font engineering in OpenType is really not much fun at all. Thankfully, good font editing tools take a lot of the pain away, and probably about 80% of the things anyone ever needs to do with OpenType layout are either handled automagically by the font editor or can be cut-and-pasted from my book.

The problem is the remaining 20%. Let’s take the example of Nastaliq Arabic. People keep saying that it’s impossible to do Nastaliq well in OpenType, but I’m not sure that’s true. (Clearly it’s not impossible.) I think it’s more likely that the tools that we have are a problem - while they let us do complex things, they don’t really help us do complex things.

The OpenType Virtual Machine

To explain this, I like to use the example of an old computer. My first computer was a Commodore PET, and it had one of these things inside it:

The MOS 6502. It ran at 1 MHz, it had 56 instructions (fundamental operations), and it was amazing. If you had an Apple IIe, an Atari 2600, or a BBC Micro (lucky you), you had one of these.

Most people programmed the PET in BASIC, but for raw power, you would program it in machine code - often using BASIC to “poke” the machine code into memory. Magazines would print long listings of games which looked like the one below, and you’d type them laboriously in by hand. You’d always make a mistake somewhere and they’d never work:

5 DATA 169,1,162,101,160,192,32,189

10 DATA 255,169,2,174,186,0,208,2

15 DATA 162,8,160,0,32,186,255,32

20 DATA 192,255,176,51,162,2,32,198

25 DATA 255,160,4,208,2,160,2,32

30 DATA 88,192,136,208,250,32,88,192

35 DATA 168,32,88,192,72,152,170,104

40 DATA 32,205,189,169,32,32,210,255

45 DATA 32,88,192,208,248,169,13,32

50 DATA 210,255,32,225,255,208,214,169

55 DATA 2,32,195,255,32,204,255,96

60 DATA 32,183,255,208,3,76,207,255

65 DATA 104,104,76,79,192,36

70 FOR T=0 TO 101: READ A: POKE 49152+T,A: NEXT

80 SYS 49152

Machine code is the lowest-level possible representation of a program. Looking at the first line, 169 refers to the CPU instruction “Load accumulator”, which tells the CPU to place the next number into a register. Then 162 is “Load X”, which places then next number into another register. And so it goes on.

Nobody writes machine code directly, though, because that would be madness. What you would do is write it out in assembly language, and have another program translate that into the DATA statements. Assembly language looks like this:

LDA 1

LDX 101

LDY 192

JSR 189

...

This is the same level as the machine code (you’re literally telling the CPU which instructions it needs to execute); it’s just somewhat easier to read. It’s a very mechanical translation between LDA and “instruction number 169”.

Needless to say people don’t like writing in assembly language. It’s not easy to see what it all means, and it’s easy to make mistakes. The subsequent development of computing has been all about moving further and further away from specifying things at the intricate, CPU level. Consider the difference between

DATA 169,1,162,101,160,192,32,189

and

if random.random() > 0.5:

print "Heads"

else:

print "Tails"

Higher level programming languages were developed which in turn required smarter compilers rather than just mechanical translation - because you’ve got to get down to those fundamental CPU instructions eventually. Until we get to today, when the compiler for the Rust language is practically sentient.

“Thanks for the history lesson, but what’s that got to do with OpenType and fonts?” Well, quite a lot.

I think of the OpenType layout system as like one of those old CPUs. The OpenType CPU has the following instructions:

| Instruction | Arguments | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

SingleSubstFormat1 |

[coveragetable], delta |

Add delta to the glyph IDs in the coverage table |

SingleSubstFormat2 |

[coveragetable], [replacements] |

Replace each glyph from the coverage table with the equivalent replacement |

MultipleSubstFormat1 |

[coveragetable], [sequencetable] |

Replace each glyph from the coverage table with a sequence from the sequence table |

AlternateSubstFormat1 |

[coveragetable], [AlternateSets] |

Same as above(!) |

LigatureSubstFormat1 |

[coveragetable], [LigatureSets] |

Look up each glyph appearing in the coverage table, identify and replace ligatures |

(and so on). In total there are 12 substitution instructions - just like in a real CPU, some of these are alternative ways of representing the same instruction - and 16 positioning instructions. Programs made up of these instructions as a set of numbers encoded in binary inside your font, just like the DATA statements in our listings above. Your OTF files contain the machine code for your OpenType CPU programs.

When you write your programs, though, you write them in assembly language. sub [A B] by [C D] is essentially a prettier and less numbery way of writing a SingleSubstFormat2 instruction, but it gets turned into a SingleSubstFormat2 instruction by a fairly low-level mechanical process. We’re still pretty close to the “CPU” here.

Higher level languages

“Yeah, so AFDKO feature language is low level. So what?” For one thing, you can’t actually use some of the instructions from the OpenType CPU because they’re not included in the AFKDO syntax. (You can’t do a ChainContextSubstFormat2, for instance.) Low-level languages are associated with raw CPU power, but that’s generally because you can get access to the full instruction set. So despite being low level, it’s not actually powerful. That removes one of the arguments for using a low level language.

But the real reason we use high-level programming languages instead of low-level ones is because they can reason about the code. This means that we don’t have to allocate our own registers, for example, because the compiler can work out the best way to do that. We don’t have to deal with the fiddly stuff. We can write our programs in terms of what we want to see happen, rather than care about how precisely to achieve it on a particular CPU.

What does this mean in the font context? The AFDKO feature language compiler (and equivalents such as fonttool’s feaLib) don’t really care what’s in your font - from the perspective of the feature compiler and the shaper, the feature code is just a list of glyph IDs which can be substituted for other IDs and have positioning information added to them. They glyphs in your font are just numbers, for all they care.

If we had a higher level language which could reason about the font, though, we could do some really interesting stuff. Let’s take the example of kerning rules. What if, instead of having to specify directly how many units to move two glyphs apart or together, we could write what we want to achieve in a higher level syntax, like so:

Create a kern for the sequence

<high initial glyph> <space> <low final glyph>which brings the ink of the main paths a distance of at least 50 units at their closest point.

A smart feature compiler will then look at the font, work out the appropriate combinations of glyphs, look at their shapes, and generate the appropriate PairPosFormat1 or PairPosFormat2 “instructions” to achieve the goal. Now we’re specifying intent, not effect - what we want, not how to do it.

Modern compiler architecture

“So, that’s what you’ve done, right? Made a high-level font engineering language?”

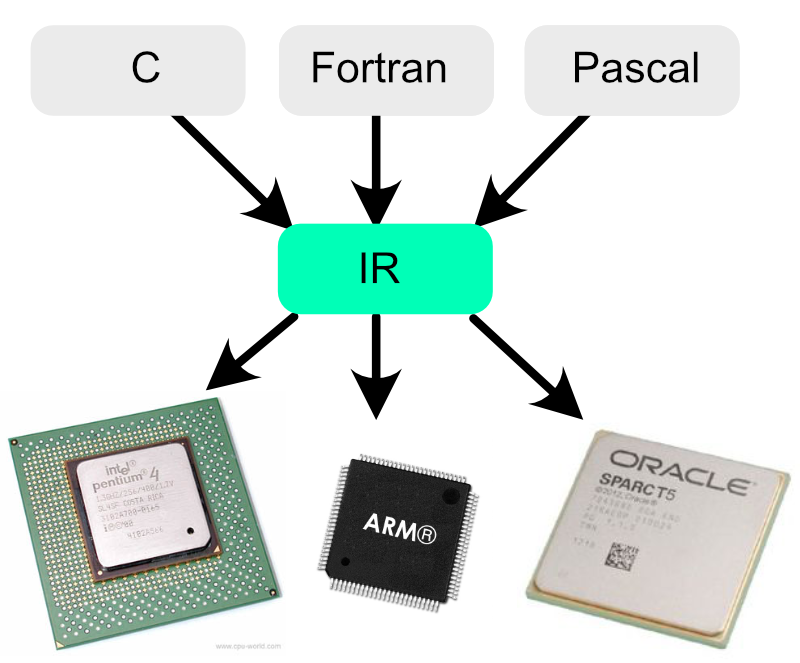

Well, yes and no. Modern compilers don’t just take in one language and output instructions for one CPU. Rather, they come in three parts: a front-end (which understands a language), a back-end (which knows how to generate machine code for a particular CPU), and a… middle-end.

This separation allows the compiler to support multiple languages on the front-end and multiple CPUs on the back-end. The idea is that the front-end parses the incoming program into a generic intermediate language - a way of representing any program that isn’t dependent on the structures of any particular programming language nor any particular CPU’s instruction set. Instead, it represents the program in terms of an idealised set of operations. The middle-end then performs common optimizations on this intermediate representation of the program, and the back-end spits out the machine code for the CPU you’re planning to use.

What I’m trying to do with the fontFeatures library is to first create an intermediate language for representing font layout operations, and then write front- and back-ends for the feature compiler.

So although the “OpenType CPU” has 28 instructions, the fontFeatures IR has four:

| Instruction | Arguments | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Substitute |

[precontext], [input], [postcontext], [replacement] |

Substitute the input sequence for the replacement sequence in the given context |

Position |

[precontext], [input], [postcontext], [positions] |

Apply positioning information to the input sequence in the given context |

Attach |

[glyphs1], [anchors1], [glyphs2], [anchors2] |

Ensure that the position of anchors1 on glyphs1 overlaps with the position of anchors2 on glyphs2 |

Chain |

precontext, input, postcontext, routinelist |

Call the given routines on each input glyph in the given context |

These are the four fundamental operations of shaping, even though they can be represented in a font in different ways. It’s the compiler’s job to work out the appropriate representation. Programs made up of collections of these operations are stored in routines; features are collections of routines. (They’re “routines” to remind you that they’re emphatically not lookups - they don’t have some of the restrictions that lookups do, like having to contain rules all of the same type.)

Frontends and the FEE Language

I’m writing a number of front-ends - components which parse the input - for fontFeatures. The first is a bit of an odd one; it’s an OTF/TTF front-end, using fontTools to pull the lookups back out of a binary font and into the intermediate representation. You’ll see why this is useful a bit later on.

Another front-end that I’m in the process of writing is a parser for the FEE language, a new font features language I basically just made up. The idea behind this language is that it’s a fairly simple and, by default, restricted language which just gives you access to the “Substitute”, “Position”, “Anchor” and “Chain” operations. Doesn’t sound very high-level, right? But it is also extensible by plugins, written in Python, which add new commands to the language, and which do talk to the font file to help compile those commands into the intermediate representation.

The Arabic plugin is a very simple one which is little more than a macro:

LoadPlugin Arabic;

DefineClass @inits = /\.init$/;

DefineClass @medis = /\.medi$/;

DefineClass @finas = /\.fina$/;

InitMediFina;

What’s going on here? Because the compiler can talk to the font, it can extract a list of glyph names and so derive glyph classes based on the naming: the @inits class contains all the glyphs which end with .init and so on. Then the InitMediFina command creates three features and fills them with Substitute rules; for each feature, it creates a synthetic glyph class and substitutes @inits~.init (which is the FEE syntax for “take off the .init suffix from each glyph name”) for @inits. Nothing too magical here - it’s just messing about with the glyph names.

The IMatra plugin is a more interesting one. A common task in Devanagari font engineering is to create a number of glyphs representing the i-matra of various widths, and then write rules which replace i-matra' *consonant* with a matra glyph which has an overhang the same width as the consonant width. Choosing the right replacement rules to match up the consonants with their appropriately-sized variant i-matra is a bit of a pain, but can often be automated in a script in your font editor. But this FEE plugin does it for you:

DefineClass @matras = /dvmI\.a.*/;

DefineClass @bases = /dv.*A$/;

LoadPlugin IMatra;

Feature abvm {

IMatra dvmI @matras @bases;

};

The plugin interrogates the width of each base, the overhang of each matra glyph, and matches them up.

The most sophisticated (and also not-quite-working) plugin at the moment is collision detection and avoidance using my collidoscope library:

DefineClass @lower = /^[a-z]$/;

LoadPlugin AvoidCollision;

Feature kern {

AvoidCollision Q @lower kern 50;

};

This… is a bit clever. fontFeatures has its own built-in terrible shaping engine which allows it to “know where things are” at a given point in the ruleset and hence make any adjustments. In this case, we run the positioning algorithm on all combinations of the letter Q and lowercase letters, and see if there are any clashes. If there are, we add a Position rule which pushes them apart so that there is at least 50 units of space between the curves. For example, when run on Adobe Garamond Pro, it detects a clash in the “Qg” pair, and adds a 105 unit kern, while the “Qp” pair only needs a 56 unit kern to provide 50 units of space between the letters. As well as “kern” you can also “raise” the glyph to kern it vertically.

These are the kind of things you can do when you’re treating the feature file syntax as a high-level language and compiling it down to an intermediate representation.

There’s one more plugin I’m working on - a FontEngineering plugin which allows you to modify the font on the fly. This is useful if, for example, you want to replace spacing marks with non-spacing marks. You don’t need to bother adding non-spacing marks to your font; just get FEA to generate them for you:

DuplicateGlyphs @marks @marks.nsp;

SetWidth @marks.nsp 0;

SetClass @marks.nsp mark;

...

Substitute @marks -> @marks.nsp;

As well as the FEE language front-end and the OTF/TTF binary front-end, I’m hoping to write two more front-ends: one to parse old-school AFDKO feature language, and one for the fontDame file format. Anyone who wants to add VOLT support is welcome.

Output formats

Currently the only back-end I’ve implemented is actually an AFDKO feature language emitter. This might seem a bit odd - wouldn’t it be better to write OTL binary into the font file? Well, I want to, but it’s hard, and to get me going I can write feature file syntax (I’m actually emitting to the feaLib abstract syntax representation, but functionally it comes to the same thing) and leverage fontTools to do the gnarly parts of actually writing to the font file. Certainly next on my todo list is to write my own OTL binary emitter, as I am starting to hit the limits of going through AFDKO. (Remember I said above that you can’t access all of the OpenType “instructions” in AFDKO?)

But the nice thing about the idea of inputting anything, storing it in an intermediate representation and then outputting anything, is that you can use fontFeatures as a kind of font engineering Swiss Army Knife. As well as compiling FEE to Adobe .fea, you can use the OTF front-end and the AFDKO back-end to decompile a font file’s lookups back into an editable representation.

Another advantage of separable front-ends and back-ends is something you get with compilers and new CPUs too. Should something come along to replace OpenType one day, or if OpenType 2.0 completely rethinks the way layout is handled (please please please), you won’t need to write an entirely new font engineering toolchain from scratch - you can just write a new back-end to translate from the intermediate representation to whatever new format you have.

Note: At present I’m doing no optimizations in the middle-end, although I will need to do so soon.

So that’s the concept behind fontFeatures. It’s still very much a work in progress and will develop over the months to come, but I hope that gives people something of an understanding of where I’m trying to go with this.