How do I learn this stuff?

I’ve been working (and tweeting) a lot about getting Nastaliq script fonts right recently, and Mark asked an astute question:

I’d be really interested in a blog post at some point as to how you do all the learning side of this, familiarising yourself with Arabic language/typography etc. and the challenges it faces.

— Mark Porter (@mrmarkporter) August 28, 2020

There are several ways to answer this, but let’s start with the embarrassing confession: when I was hired to work on engineering a Nastaliq font, I could barely read the script at all. I’d got a little bit of Arabic experience to get SILE to typeset it correctly, but nothing really more than understanding joining behaviour and bidirectionality issues.

Now to mitigate that statement slightly, I’m only the engineer, and I’m working in a team with a highly skilled designer and some really good language consultants. There is spirited debate about the amount of script experience needed to design a font for which you are not a native user, but that doesn’t apply to me; I know that I don’t have the script-cultural understanding required to design for Arabic or Urdu, and I wouldn’t even try. But I don’t have to, because that’s not my role. So that leads to one way to answer the question “how do I learn about the requirements of Nastaliq font engineering?”: I work in a team, I ask people, and they tell me.

The background that I had already, for getting SILE working, was mostly picked up through reading things like the Unicode Standard(PDF) chapter on Arabic. When beginning to work with a new script technically, grabbing the appropriate chapter of the Unicode standard is a fantastic place to start. It tells you about the requirements that needed special consideration when encoding the script, and some of the areas that you need to consider as a developer. Learning the technical stuff of how Arabic is shaped through the OpenType system, Microsoft’s script development spec is a really useful guide. In fact, I had gathered a list of helpful localisation reosurces when writing my “Fonts and Layout” book.

But for a font engineer, you need more than just technical understanding of the script and how it is processed. For one thing, you need to have a sense of whether the output you are producing “looks right”! Your designer and team mates will tell you that, obviously, but you can iterate much faster if you already have a sense of what is working and what needs to be fixed.

To attain this, I went through a deliberate process of familiarisation. The first two months of working on the font was basically getting to know the script.

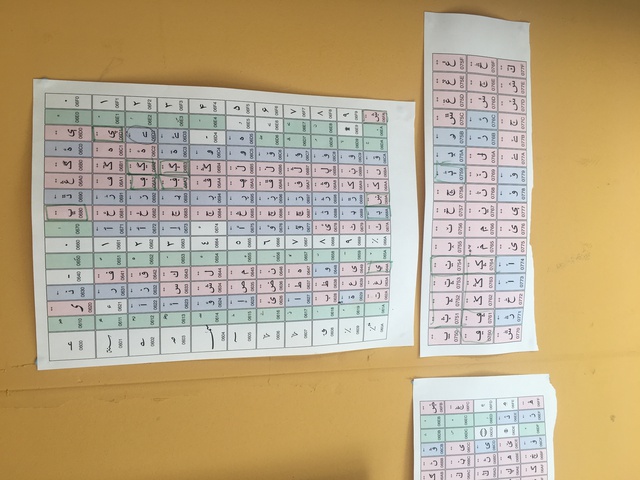

A very basic step one: I printed off a number of different charts of the Arabic/Urdu character set and pinned them on my wall. Here’s one:

This one is colour-coded according to joining group. Others were separated out by characteristic. (rasm / dots above / dots below / etc.)

Step two: I joined online courses in Persian and Urdu. This isn’t strictly necessary - I need to know the script, not necessarily the language - but it’s all part of the familiarisation process. I have to say that the Persian course was a better experience, so I have kept up that one and dropped the Urdu. It helps that it’s also more directly relevant to the rest of my life: we are getting to know a number of Iranians and speakers of other Indo-Iranian languages (Kurdish Syrians, etc.) around Gloucester, we have contacts with Iranian churches, and so on. Who knows what I will be doing with this knowledge when I finish this project…

Step three: Read. The best way to learn any language is immersion, and I think the same is true of scripts. To get a feel for what’s right and what’s wrong, I needed to get a lot of Urdu and Persian text in front of my eyes. I got hold of Bibles and books of poetry in each language and spent a long time just looking through them, picking out salient features, and beginning to recognise each of the letter forms. Sometimes I would try to read each letter out loud until I was able to recognise some sight words (it helps that my son is learning to read right now as well!); other times, I would just let the text wash over me and get a feel for the “rhythm”. I got an audiobook version of the Urdu New Testament, and listened to someone else read out the text, trying to follow along.

Alongside step three, I looked at other implementations of Nastaliq fonts (and some Arabic fonts) and how they worked. (The first step in writing fontFeatures was writing something which took in a binary font and turned it back into readable feature code.) This gave me a sense of what the requirements were and what areas seemed to be the most difficult to implement: if half of a font’s feature code is handling the bari ye sequence, then that’s probably a significant issue in font engineering.

Doing this together with the reading meant that I was connecting the technical requirements with the typographic usage. I could look at a bit of text and say “Oh, hey, they’ve obviously needed to separate the horizontal dots there to stop them from clashing.”

Step four: Write. I had gotten hold of some calligraphy manuals already and started trying to copy some of the shapes. (Then my consultant told me they weren’t particularly good and suggested some others…) My calligraphy is still totally bleh, but again, it’s all part of developing a feel for the script - how it works, how it flows, and gaining familiarity with the letterforms.

Now I do a bit of all of the above - Persian lesson first thing, a bit of doodling letterforms during downtime, reading the Persian New Testament in the evening, (yes, I know - I’m working on an Urdu font, not a Persian one; that particular stylistic distinction is the designer’s problem, not mine…) and printing out and comparing proofs during the day. It’s basically the geek way: decide what you need to obsess about; focus deeply on it; repeat as needed.

To be honest, I still do not consider myself anywhere near fluent with the script. I can just about read (although I don’t have much sense of the meaning). I’d like to be better in this, and will keep learning. But more to the point, from a font engineering perspective, I’ve got to the point where I know what I’m looking out for, and what the issues are. Once I had a feel for what I was supposed to be doing, it was just a matter of iterating, comparing my output against output from other fonts, getting feedback from others in the team, and continuing to develop my feeling for the script that way.

(In another blog post, I’ll try and write up my engineering iteration and proofing process, because I think it’s probably different from everyone else’s; I find it really efficient, and I think it’s another reason I’m able to get this stuff done quickly.)