Five Rust tips for Python Programmers

I’m writing a lot of Rust these days, including a bunch of font tooling in Rust. If you haven’t looked into Rust, now is the time. There are quite a few of us in the font community playing with it, and I imagine there will be strong pushes in the future to move more of the font ecosystem in the Rust direction. Two new open source font editors - runebender and MFEKglif are both written in Rust, and I’m working on a Rust font building toolchain which is literally hundreds of times faster than Python fontmake. (I’d love to be able to say “thousands”, but not there yet; still, it’s fast enough that I get antsy when I have to wait more than three seconds for a font to build.)

Of course, Python was the primary font engineering language, and I imagine that will remain so for quite a long time. And Python is much friendlier for people coming from a design background than Rust. But for backend stuff, Rust is, I’m convinced, the future. So what would I recommend for people coming from Python and looking into Rust? I’m still a learner myself, but here are five tips that I have found which will make the whole journey easier.

Pointers go one way

By far the biggest shift going from Python to Rust is the data model. Yes, the data access model - borrowing and exclusive mutability - is a big shift, and we’ll come into that, but if you get your data model right, most of your data access model worries go away.

In Python, you’re using to using references everywhere. If you have a font which has glyphs and the glyphs have layers, you can say font.glyphs[0].layers[0] and you can say layer.glyph.font. It’s not just that the font has glyphs, but the glyphs also have a font. And you can navigate around the whole structure with these bidirectional references, and everything is lovely.

I’m completely serious: If you keep that data model in your programming practice while trying to use Rust, it will hurt. You will find yourself trying to stash references to things in inappropriate places and the borrow checker will get upset and you’ll start worrying about lifetimes and Rcs and Boxes, and soon you’ll be thinking that this is a horrible language that you don’t want to work with.

In Rust, data is hierarchical. A font has glyphs. Glyphs have layers. And so methods also have to be hierarchical. A function on a layer can’t look sideways at other layers or upwards at the glyph. If a layer needs to know something about its glyph, then the method needs to be written at the glyph’s level.

Practical example: I have a designspace library. A designspace has sources and axes. I want to normalize the source’s location. From a Python perpective, I start with

class Source:

def normalize_location(self):

...

because the location is the property of the source, right, so that’s a sensible class to have that method on? Ah, but the min/max/default values for each axis, which I need to know if I’m going to normalize the location, belong to the axes, and the axes belong to the designspace, and here in Source I can’t see the designspace. So normalize_location either has to live somewhere which can see both the axes and the sources - i.e. at the Designspace level - or it has to have the axes passed into it.

Better to have it at the Designspace level rather than to pass the axes in, because while this is a simple method, once you start mutating objects, you will find that having two different parts of the same data structure coming from two different locations is a recipe for borrow problems.

Rust talks about the “radical wager”: if you swallow some unpleasant-sounding programming philosophies up-front, then everything else becomes considerably more pleasant, and I think it’s right about that. In my fonttools library, I barely use references at all. All the data is stored in structs which directly contain other structs.

Where do you want your data?

A short note on references: if you’ve ever done any C programming, you’ll recognise the & operator as something that takes a reference or pointer.

Forget that.

The difference between compute(thing) and compute(&thing) is about where the data ends up. If you call compute(thing), you give thing away and you can’t use it any more. If you call compute(&thing), compute is borrowing thing and it’s still yours to use again.

Thinking “where do I want this data to be?” and using & appropriately will fix a whole host of compilation errors.

Learn to love the lints

cargo clippy is amazing and you should use it.

Clippy is a very high-level code analyzing linter. It doesn’t just do simple stuff like telling you off when you call variables foo but it can do some extremely sophisticated analysis, finding quite specific patterns. It basically teaches you how to write better code.

Not only that, but it often tells you how to fix the problems as well, and can refactor your code for you to make it better.

Your editor is your friend

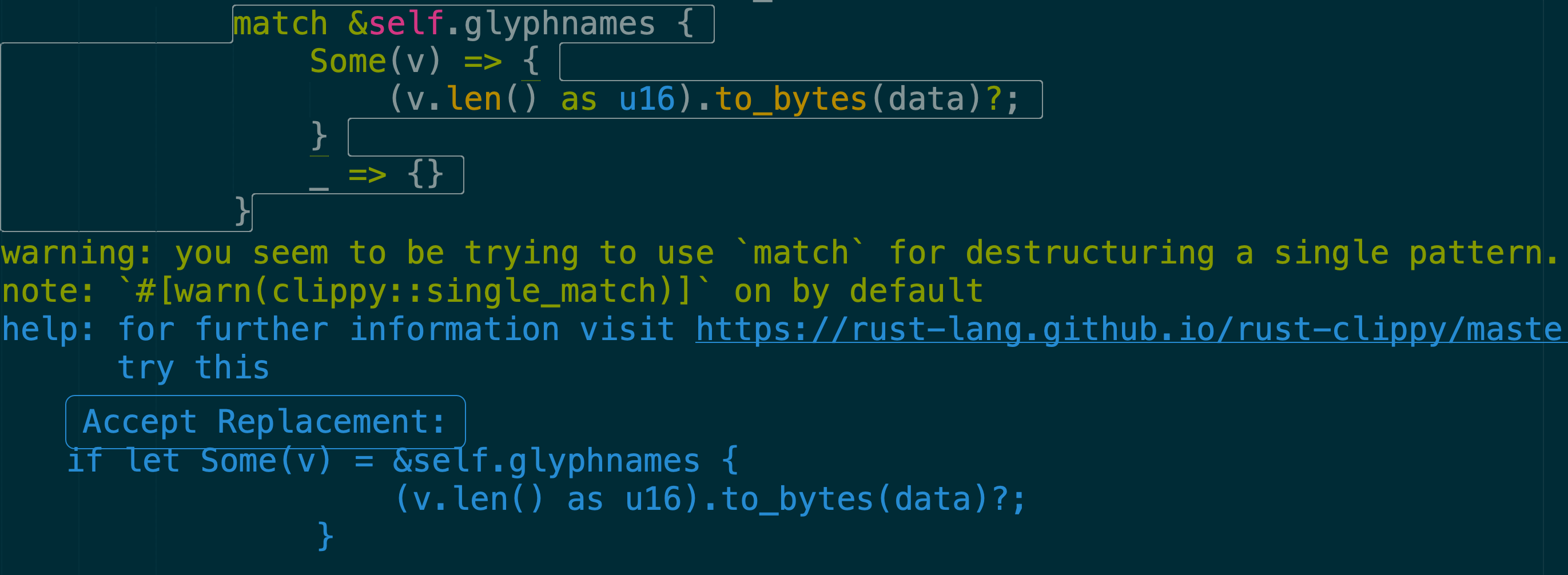

I use Sublime Text’s Rust Enhanced package, which gives me Clippy lints every time I save, as well as a big blue button to apply the fixes it suggests:

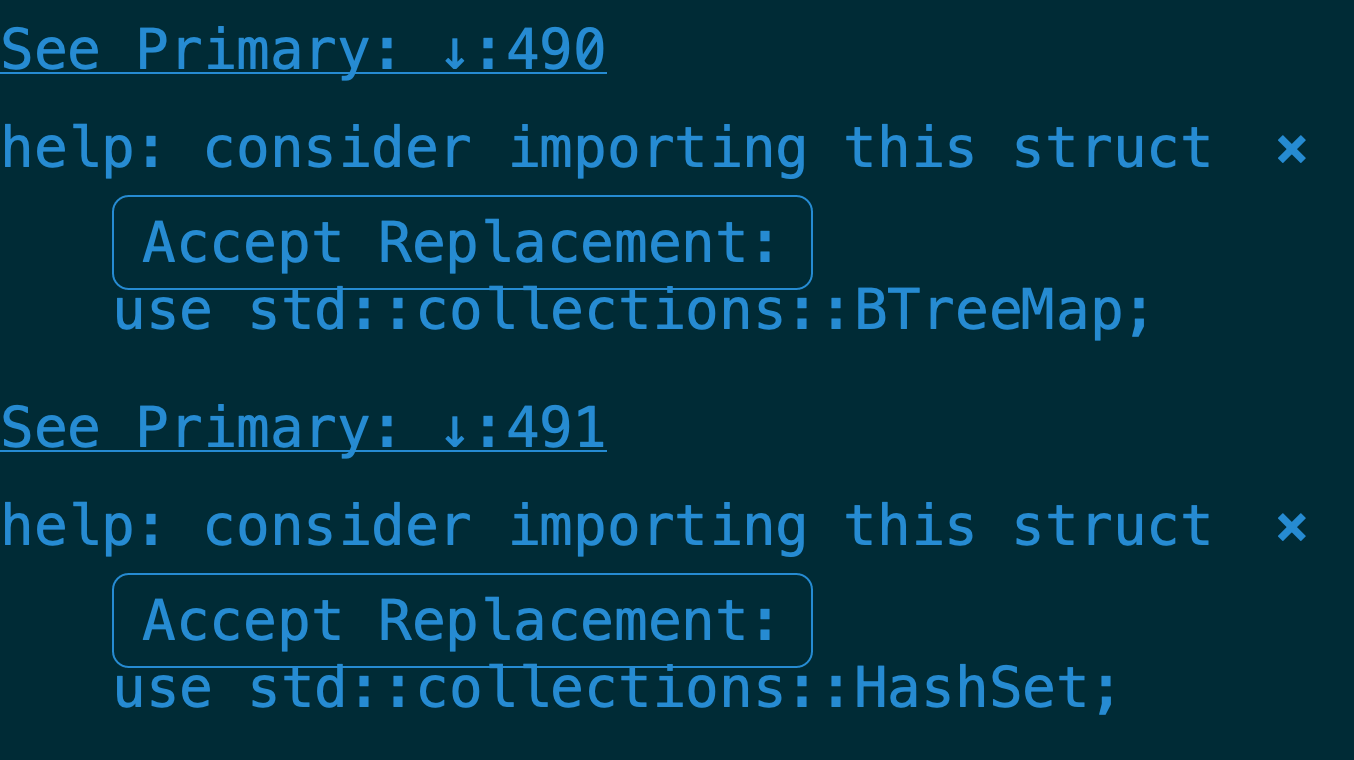

It also runs rustfmt on save (which is a Good Thing), and suggests fixes for many common warnings, including providing pretty good suggestions for times when you’ve forgotten to import particular items or traits:

Basically it takes the feedback from the compiler (which is generally excellent) and displays it at the appropriate locations in your codebase, and gives you the option to fix it.

Other editors are available, but yours should at least do this.

You should also install Rust Analyzer which gives you tooltips when you hover over variables and methods so you can check their types.

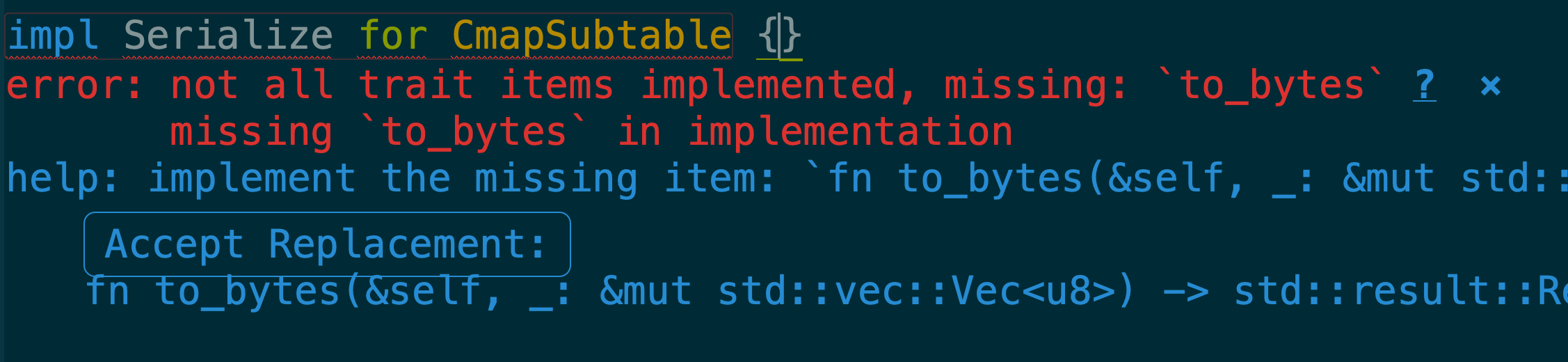

Because of this feedback loop with the compiler, I very often write deliberately broken code to get the editor to fix it for me. If I’m not sure what the type of a function should be, I guess, hit save, and the editor says “Nope, should be Option<&Vec<Whatever>>”, and then I use that instead. Or I can’t be bothered to look up all the functions I need to implement a trait and their signatures, so I just write an empty impl block and hit the blue button to fill in the code stubs I need:

Every time I hit save, there’s a compile step, with warnings, suggestions and fixes. Yes, if I were a better programmer, I wouldn’t need all these supports. But I’m not, and right now I cannot imagine writing Rust without this. And you know what, that’s OK.

Your code is good code

Turning back to Python for a moment, designers and other programmers sometimes people show me their Python code and they ask me, “Is this the best way to do it?”

And sometimes there are some refactors that I might like to make, and sometimes there are ways that I might approach a problem completely differently. But I normally try to stop myself from doing those things, and instead say something like this: “If the code does what you want it to do, and it’s code that you are capable of writing and understanding, then it’s good enough.” I mean that. The best code is code that works and code that you can write. Anything else is a bonus.

The same is true in Rust. I am sure that a more accomplished Rustacian could write my code more efficiently, more cleanly, and so on. But right now, I can’t. So my code is the best code that I can produce. And it works. (More or less.) So I’m happy with it.

I’m definitely doing way too many allocations. I don’t know when I should be using .clone() or .copied(). I gather iterators and call .collect() and then pass the result to another iterator. It’s all a mess. But I wrote it, and it works. It could be optimized, I’m sure. And if someone can make it 200 times faster than Python instead of 100 times faster than Python, that’s great, but really, in the grand scheme of things, it’s pretty immaterial. I’m not going to sweat it. And neither should you.

Just write code. And enjoy it. Do all the things I’ve mentioned above and you’ll enjoy it a lot more.