Automated Kerning for Nastaliq

One of the funny things about programming is that you can take an operation which is fundamentally pretty dumb stupid, and by doing it in an automated and methodical fashion, come up with a result that is quite impressive.

For example, the whole premise of machine learning is that if you get things wrong millions of times you eventually start getting them less wrong. We can start playing a game with completely random moves and no built-in understanding of the rules, and just by doing things wrong enough for long enough, come up with a program which can defeat world class go players.

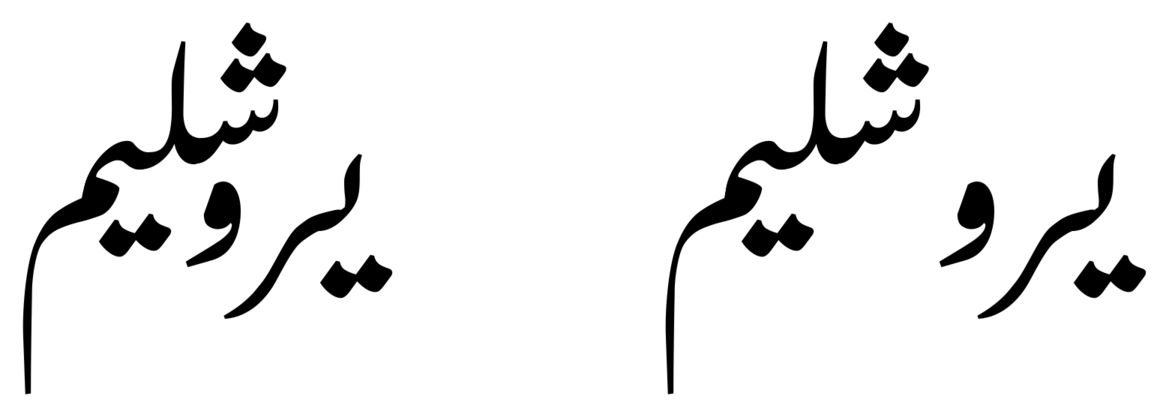

I recently demoed some code which automatically creates kern rules to compact the word-shapes of a Nastaliq font, like this:

and I am here to tell you that the impressive-looking result is actually just the result of doing something dumb-stupid lots of times.

How do we make a Nastaliq auto-kerner? I’m going to clean up and release the full code a bit later (you’ll find an IPython notebook later in this post with a very rough version), but let’s look at the fundamentals here.

Framing the problem

In Nastaliq style, the final glyph of a sequence is placed on the baseline, but preceding glyphs are connected almost diagonally so that they rise up above the baseline, like so:

This is a made up sequence, but you can see that the final glyph is “up in the air”.

But with a shorter or longer sequence, that initial shin (س) may appear at a different height:

Here is the challenge of Nastaliq kerning: when another word appears before a “high” sequence like these, there might be a lot of unused room between the baseline and the initial glyph (the one on the right) in a sequence.

Just like in Latin kerning, these large gaps are considered unsightly, and the space should be filled up. So we need a kern. The only problem, of course, is that this kern is not just pair-wise between the glyphs س and ر, but is highly contextual, and depends on the height of the س, which is determined by the rest of the sequence. Imagine if, when writing a Latin kern pair, you had to take the whole rest of the word into account. How would you do that so that it worked for every possible word?

Now I’ve already promised you that the answer is going to be dumb-stupid, so you can relax. There really isn’t very much trickery here at all.

Let’s begin by breaking it down into two sub-problems: determining a single kern pair, and determining all the kerns.

Determining one kern

To determine a single Latin kern, I need two parameters: left glyph and right glyph. I can’t determine that automatically yet because Latin kerning is weird, but in theory it’s simple - it just depends on these two glyphs. To determine a Nastaliq kern, such as the one between the س and the ر in this example, I need three parameters: the left glyph, the right glyph, and the height at which the left glyph appears. As you can see from the previous image, the height will determine the size of the gap we need to fill.

So our output is going to be a three-level kerning table: every possible left glyph against every possible right glyph against every possible right-glyph height. Don’t worry about that for now.

Let’s assume for now that, by some magic, we know the height that a right glyph appears. How do we work out the kern which fills the gap?

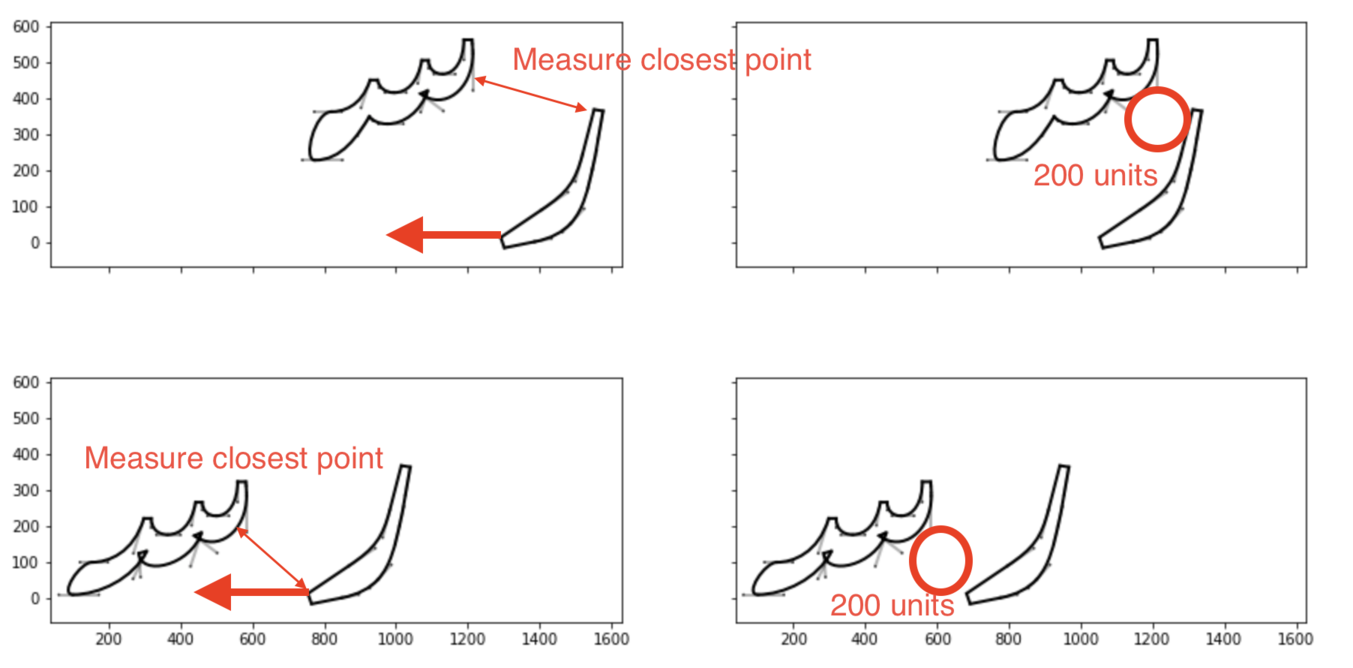

Conceptually, this is very simple. We take the Bezier paths for the two glyphs, and we slide the right glyph horizontally until it comes within a requested distance of the left glyph.

And it really is as dumb-stupid as that. I take the Bezier paths, keep moving the right glyph left, check the distance at the closest point - which I do in a very dumb-stupid way by measuring the distance between every segment on one path and every segment on the other and finding the minimum, because computer run time is cheap and programmer thinking time is expensive - and repeat, stopping when I have got to the appropriate distance.

There’s only one slightly clever thing here, which is that glyphs above a certain height are never going to come within 200 units of each other, so you have to decide a maximum distance at which to stop. You probably don’t want to go much “deeper” into the “hole” than 50% of the width of the left hand glyph, because you’ll mess up anything that comes to the right, so we set a stopping distance as a percentage of the width of the left-hand glyph.

And that’s it; we basically implement Bubblekern in the stupidest possible way.

Determining all the kerns

So we can make one kern for a pair of glyphs (and by iteration we can create a kern table for all relevant pairs) if we know the third variable, the height of the left-hand glyph. Let’s assume, again by magic, that we have at our disposal all of the kern tables, one table for each of the heights that we’re going to need. We have a kern table which applies at height=172 and a kern table which applies at height=613 units, and every other height of every possible word.

Now all we need to do, right, is just need to compute the height of every single possible word, and create a contextual chaining rule which dispatches to the appropriate kern table. Easy!

Again, let’s break this down into two subproblems.

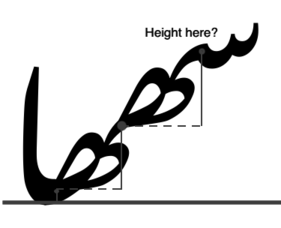

What is the “height” of the left glyph in a pair, that is, the height of the initial (rightmost) glyph in a sequence? From the picture below, we can see that we just sum the rise - the distance between exit and entry anchors - for all of the glyphs in the sequence after the initial glyph.

Given the sequence and the total height - in this case, 685 units high - and remembering that we magically have a kern table for every possible height, we can very easily construct our contextual rule:

pos @isols_and_finals' lookup kerntable_at_685 SINi5' HAYAm4 HAYAm3 ALIFf1;

This notebook shows the general principle of computing the height of a sequence and then determining the kern value for a kern pair.

Now of course we’re not going to generate every single word image and every single height, and every single kern table. We’re going to approximate. My glyphtools Python module has some code for clustering glyphs by property, and one of those properties is the rise value. So we can now autogenerate a set of classes of glyphs based on their average rise, replacing the above with:

@finas_rise_65 = [ALIFf1 DALf1 GAFf1 HAYCf1 KAFf1 TOEf1];

...

@medis_rise_334 = [AINm1 AINm2 ... HAYAm2 HAYAm3 HAYAm4 SADm17];

...

pos @isols_and_finals' lookup kerntable_at_733 @inits' @medis_rise_334 @medis_rise_334 @finas_rise_65;

This is now looking both a lot more general and a lot more tractable - we have a small number of finas and medis classes organised by average rise, and we can generate all combinations of possible heights (and contextual dispatch rules) from arbitrary sequences of glyphs. But that’s still a lot of combinations of total rise, and hence quite a large number of kern tables needed.

We make four more approximations to simplify matters.

- Within each kern table, we round each kern to the nearest 5 units, which turns a lot of individual kern rules into a smaller number of class kerning rules.

- We round the sum of the rises within a sequence by a particular quantization value - let’s say, 100 units - and we now find we only have to build kern tables for total rise =

[0, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900...]. - We notice that once the gap is larger than the size of the tallest final/isolate glyph, any higher sequences are going to be identical. So in our case, everything over 600 units high will just dispatch to

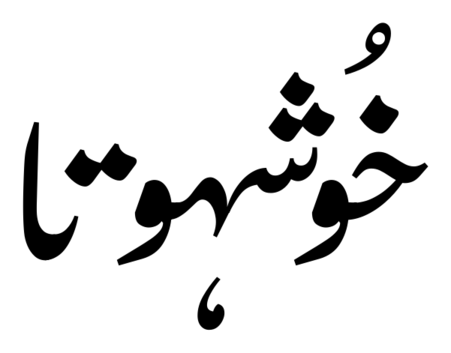

kerntable_at_600. - Any short sequences on the left whose final glyphs are “bari-ye-like glyphs”, which have large RSBs which sweep back over the glyph sequence, don’t get any kerning. This is because those bari-ye-like glyphs may well end up occupying the empty space, like so:

We still have to compute seven complete kern tables, each containing kern values for every initial glyph against every final/isolate - and it still takes around half an hour on my computer to produce - but when compressed they come to around 11,000 lines of feature code, which is a lot fewer than the several million lines I started this experiment with.

And the result is quite pleasant

even if the implementation is as dumb as a box of rocks.