COLRv1 and Rethinking Variations

OK, here’s the lead - you can do amazing things with COLRv1 fonts:

This is a glyph from a variable font, animated with CSS. COLRv1 enables us to do some amazing things.

— Simon Cozens (@simoncozens) September 19, 2022

Blog post coming soon. pic.twitter.com/sUi1pj78AE

In case you don’t believe me, grab the latest version of Chrome, go to chrome://flags/ and turn on “Variable COLRv1 Fonts” and take a look at this:

In this post I’m going to run through what COLRv1 is, how I did the above, and also what that means for how we think about variable fonts.

COLRv1

I’ve been basically ignoring colour fonts since forever, but recently I got nerdsniped into looking at COLRv1 for animations. Animated fonts may not exactly be what the world needs most right now, but the fact that they can be implemented in COLRv1 shows just how powerful this format is.

If you’ve seen or worked with colour fonts before, you may know how COLRv0 worked: each COLRv0 glyph is made up of coloured layers, which are each independent glyphs. You define a colour palette (or more than one), and you tell the font to associate a colour with each layer, and then they all get composed together.

And that’s basically all you can do.

COLRv1, on the other hand, is completely different. It’s billed as an extension to COLRv0 to allow for colour gradients, but that’s really selling itself short. In fact, if you read the colour gradients spec you will discover that COLRv1 was designed essentially to take the basic paint operations of a vector graphics composition system - something like SVG, for example - and make them available inside a font.

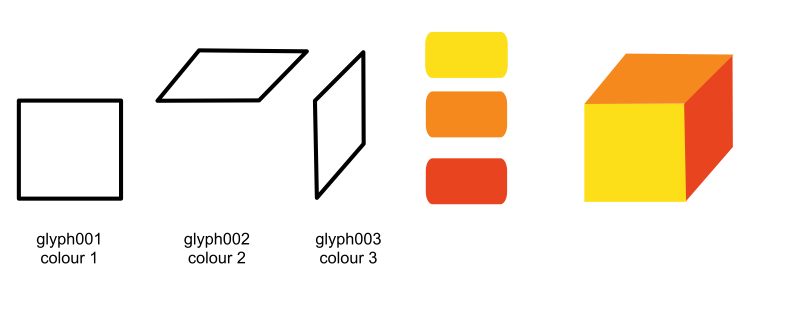

These basic operations are called Paints in COLRv1, and they’re all connected together. I made a little toolkit for creating COLRv1 paints to make the animation above, and it uses a kind of Python function composition syntax to represent connecting the paints together. Let’s take a quick tour of the paints available:

-

To get the same behaviour as COLRv0, you use a

PaintGlyphpaint to specify what shape you’re drawing, taking the shape from the curves of another glyph in the font, and connect it to aPaintSolidpaint. In my syntax,PaintGlyph( "square_front", PaintSolid("#FDDF19FF") ). -

You can also use a

PaintColrLayerspaint to draw a combination of paints together:

PaintColrLayers([

PaintGlyph( "square_front", PaintSolid("#FDDF19FF") ),

PaintGlyph( "square_top", PaintSolid("#F5891DFF") ),

PaintGlyph( "square_side", PaintSolid("#E94420FF") )

])

-

So far, so normal. You can also add linear gradients, the ostensible reason for the COLRv1 upgrade, with the

PaintLinearGradientpaint, as well as radial and sweep gradients. -

Once you’ve defined a glyph using these paints, you can also paint that colour glyph inside another colour glyph, using the

PaintColrGlyphpaint. -

And now it gets really fun.

PaintTransform(and its friendsPaintTranslate,PaintScale,PaintRotate,PaintRotateAroundCenterandPaintSkew) can move, scale, rotate and deform a paint. So we could actually make the above cube just by using one “outline” glyph, the front square, painting the same glyph onto the top and sides but deforming it:

PaintColrLayers([

PaintGlyph( "square_front", PaintSolid("#FDDF19FF") ),

PaintTranslate( 100, 0,

PaintSkew( 45, 0,

PaintGlyph( "square_front", PaintSolid("#F5891DFF") )

)

),

PaintTranslate( 0, 100,

PaintSkew( 0, 45,

PaintGlyph( "square_front", PaintSolid("#E94420FF") )

)

)

])

- Last, but by no means least, there is

PaintCompositewhich composites one set of paints onto another, using any of the W3C Compositing and Blending Level 1 compositing modes. That means alpha blending, boolean operations, and all kinds of graphics wizardry that I don’t claim to understand.

And the best bit? All of these paints have variable counterparts, so that you can change how they operate across the scope of the designspace. So if you want to add a shadow to your glyph which gets bigger as you go down the SHDW axis, you don’t need to draw two masters of your shadow path and interpolate between them; instead, you can draw one glyph representing the shadow, and you can use PaintVarScale to enlarge it, skew it, or whatever else as the font varies:

PaintVarScale("SHDW:0=0.0 SHDW:0.9=0.0 SHDW:1=1.0 SHDW:10=2.0",

PaintVarSkew("SHDW:0=0.0 SHDW:0=1.0 SHDW:10=45.0", 0,

PaintGlyph( "shadow", PaintSolid("#333333AA"))

)

)

Well, when I say “you can do that”, obviously you can do that in the sense that the OpenType format allows for this combination of paints. But you probably can’t do that in your font editor. Sorry.

The Lottie convertor

So how did I manage the fire emoji above, then? There’s an file format called Lottie, which is a JSON based format for 2D animation. You can get After Effects plugins which export it, and build JavaScript players to show them on the web, or whatever. But you can also turn it into fonts.

Because COLRv1 is built around fairly standard graphics primitives, and Lottie is built around fairly standard graphics primitives, it’s not too difficult to write something to convert Lottie into OpenType. As we parse a Lottie file, we go through a number of steps: the Shape layers get converted into Bezier paths, and we write those onto a FontTools pen and store them as separate glyphs; all the other layers get converted into COLRv1 Paints, first through my Python-like Paint syntax, which then turns into the JSON-like Paint syntax used by FontTools’ colrLib.builder, and from there into an actual COLRv1 table. Finally, fontTools.fontBuilder is used to create the other tables which make up an OpenType font.

(fontmake is cool and all, but more people should use fontTools.fontBuilder to build fonts by hand. You don’t actually need UFOs to make a font, and sometimes it’s easier not to.)

The only real bit of magic is that in Lottie, properties such as a scaling transformation can be animated, and these get turned into a string like the one we’ve seen above: "SHDW:0=0.0 SHDW:0.9=0.0 SHDW:1=1.0 SHDW:10=2.0". These values at different positions in the designspace are encoded and stored in an Item Variation Store, which is handed to colrLib.builder when we save the COLRv1 binary.

And that’s where things get interesting.

Rethinking Variable Fonts

OK, so maybe animated emoji aren’t necessarily an appropriate use of this technology (although it is pretty cool to have them working in a browser with just CSS and a font), but thinking about how to build animated emoji has, I think, the potential to give us a new perspective on variable fonts.

From a traditional font design perspective, when you have a variable font, you have masters. Masters represent the concrete realisation of what a font looks like at a certain point in the designspace. You draw the font as it looks at wght=400 and you draw the font as it looks at wght=800 and the computer fills in all the points in the middle.

And that is how we have used variable fonts so far. All of the points on an outline vary all at once, and they all vary in the same direction. All of the outline points in the regular master move towards the equivalent points in the bold master as we move from wght=400 to wght=800.

But this is not how animations work at all. When you’re creating an animation in animation software, you don’t draw all the elements for the first frame, then all the elements for the second frame, and so on. Instead, each element - the body, smile, the individual beads of sweat - have attached to them a set of keyframes for each aspect of their motion. Each bead of sweat has separate keyframes for its opacity, so that it comes in and out of view at certain times, and different positions for its position, so that it moves around to different places at different times. In an animation, you say that at time=0 the element has position x_1,y_1 and at time=50 the element has position x_2,y_2.

This is an excerpt from the paint definition of the fire emoji:

PaintVarTranslate(

"ANIM:97=35 ANIM:129=16 ANIM:147=42 ANIM:182=16",

"ANIM:97=211 ANIM:129=154 ANIM:147=105 ANIM:182=57",

PaintVarRotate(

"ANIM:98=0 ANIM:118=5 ANIM:138=-14 ANIM:161=0 ANIM:182=-15",

PaintVarScale(

"ANIM:97=0 ANIM:131=1",

"ANIM:97=0 ANIM:131=1",

PaintGlyph("glyph0016", ... )

)

)

)

How many masters are there in this situation? Well, it’s difficult to say. It’s the wrong way to think about it. Unlike in a traditional master-based font situation where all the points vary all at once, all in the same direction, different parts of the paint are varying at different rates and in different places. I suppose you could say that each individual paint has its own set of masters: four masters for the translation, five for the rotation, and two for the scaling; but they’re all at different points in the designspace. So there aren’t really masters in the sense of particular locations where there is a concrete instantiation of what the glyph looks like at that point.

The fact is that, as we’ve demonstrated above, OpenType Variations actually already allows us to do this. Any aspect of a variable font - any point, any paint, any kern, any positioning rule, any substitution - can have its own set of masters, its own set of keyframes, representing values at different points in the designspace.

This is what I call “masterless design”, and I think that it’s a concept that’s actually very applicable not just to crazy stuff like animated emoji but also to typeface design. One of the tricky parts of creating variable fonts is that you first need to know how many masters you need up-front; you also have to make sure to keep your paths compatible in all your masters.

But if we get rid of the concept of masters, and just have a path that has a set of keyframes describing how each point varies, a lot of these problems go away. First, your path is guaranteed to be compatible across masters, since there is only one path and only one master. And second, if you need to tweak certain points in certain glyphs at certain places in the designspace - something you would need an intermediate master or alternate layer for in a master-based design - it’s very easy. You don’t need a new master; you just add a “keyframe” for the particular point or points that need to change, specifying when they need to change and how, and you’re done.

This is something that’s actually much easier to surface in our font editors than all the clever things we were doing with paints. In fact, a while back I created a little demo of what a masterless font editor might look like.

In short, there’s a lot more to explore in colour fonts than I think we have explored so far; and I think there’s actually a lot more to explore in variable fonts than I think we’ve explored so far.

Or we could just enjoy the pretty emojis. a